Chief Justice Ramana Demands Proper Judicial Infrastructure in India

Chief Justice Ramana said that people’s faith in the judiciary is the biggest strength of democracy and courts must protect people’s right to justice.

By Rakesh Raman

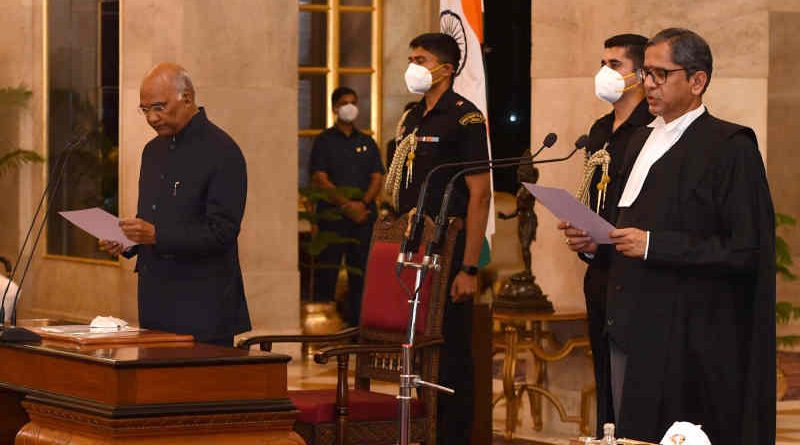

The Chief Justice of India (CJI) N.V. Ramana raised several concerns over judicial infrastructure as he shared the stage today (October 23) with Law Minister Kiren Rijiju. He urged the Law Minister to make sure the proposal to set up the National Judicial Infrastructure Authority is taken up in the winter session of parliament.

The Chief Justice said that judicial infrastructure is important for improving access to justice, but it is baffling to note that its improvement and maintenance was being carried out in an ad-hoc and unplanned manner in the country. He also commented that an effective judiciary can help in the growth of the economy and courts are extremely essential for any society that is governed by rule of law.

CJI Ramana was speaking at the inauguration of two wings of the annexe building at the Aurangabad bench of the Bombay High Court. He complained that courts in India still operate with dilapidated structures, making it difficult to perform effectively.

Commenting on the lack of infrastructure, he said that in India only 5 percent of court complexes have basic medical aid, 26 percent of the courts do not have separate toilets for women, and 16 percent of the courts do not even have toilets for men. Also, nearly 50 percent of the court complexes do not have a library and 46 percent of the court complexes do not have the facility to purify water.

While it is largely believed that there is an increasing level of political interference in the functioning of the Indian judiciary, Law Minister Rijiju said there is no politics when it comes to judiciary.

Citing international research published in 2018, Chief Justice Ramana pointed out that the “failure to deliver timely justice can cost the country as much as 9 percent of the annual GDP”. He added that this loss to the economy cannot be averted without adequate infrastructure for courts.

Supreme Court judge Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, who was also present at the event, said that the judiciary is confronted with the issue of pending cases in the state and the country. He pointed out that there are over 48 lakh (4.8 million) cases pending in Maharashtra with around 21,000 cases being more than three decades old. But he did not offer any solution to address the issue of the pending court cases.

Justice Chandrachud highlighted the importance of virtual courts which – according to him – can help citizens across the nation gain access to court proceedings.

INCOMPETENT INDIAN JUDICIARY

While India is increasingly becoming an authoritarian state, the judiciary has almost lost its credibility because most judges are complicit in state crimes and do not take action against the crimes of the ruling class. Chief Justice Ramana said that people’s faith in the judiciary is the biggest strength of democracy and courts must protect people’s right to justice.

But such rhetoric in academic lectures or inauguration events cannot solve the persisting problems in the Indian judicial systems. Since Indian lawyers and judges are working in a casual, free-wheeling manner, the Indian legal system is plagued by random judgments and long delays. As a result, there is a backlog of nearly 4 crore (40 million) pending cases in the Supreme Court, various high courts, and the district and subordinate courts.

Reports suggest that the pending court cases in India have been rising rapidly during the past over one year when the courts became even more sluggish during the coronavirus outbreak.

Moreover, it is being increasingly observed that the Supreme Court of India judges are scared of crooked politicians who virtually control them. When the case is against the government politicians or top officials connected with the politicians, the judges do not take any decision that may displease their government bosses.

In some cases, they issue perfunctory notices to the government or casually censure the government lawyers to hoodwink the citizens. But they never use the law to punish the criminal politicians or their accomplices. The cases in which the politicians or top bureaucrats are accused never get decided and rather get lost in the oblivion.

However, when the authoritarian rulers harass or imprison their critics illegally, the judges never try to rescue them. Rather, they waste plenty of time in useless hearings or deferments so that the government critics must languish in jails without proper trial.

But when the criminality of politicians comes in front of them, instead of putting them behind bars, the judges always tend to agree with the government lawyers and complicit police officials so that the criminal politicians could be protected.

Today, it largely depends on the whims of a judge who can accept, reject, or defer a case without giving any reason for their decision. Instead of simply following the law, Indian judges perform as preachers in courts to advise the culprits while their loose statements have no legal relevance. Worse, most judges behave as demigods and their arbitrary decisions cannot be challenged.

As the Indian judicial system has lost its credibility, the judges are frequently denying bails to the accused, ignoring habeas corpus petitions, delaying crucial cases that impact large sections of the society, and arbitrarily dismissing crime and corruption cases filed against the government politicians.

It is highly unfortunate that the Supreme Court judges only talk about the rights of citizens in their academic lectures outside the court. But when they sit in the court, they fail to protect citizens’ rights. Rather, they protect criminal politicians.

If you evaluate the Supreme Court judgments (involving the government) through an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based expert system, you will find that almost all the judgments or delays are biased in favour of the government.

The same evil trend is being observed in other courts of India. Obviously, the Indian judiciary is not in safe hands.

By Rakesh Raman, who is a national award-winning journalist and social activist. He is the founder of a humanitarian organization RMN Foundation which is working in diverse areas to help the disadvantaged and distressed people in the society.