Crowdsourcing to Fight Spread of Fake News in Politics

Crowdsourcing to Fight Spread of Fake News in Politics

Fake news isn’t a new problem, but it’s becoming a greater concern because of social media, where it is easily created and rapidly distributed. A recent study by MIT Sloan School of Management Prof. David Rand and Prof. Gordon Pennycook of the University of Regina finds there is a possible solution: crowdsourcing.

As their research shows that laypeople trust reputable news outlets more than outlets that create misinformation, social media platforms could use trust ratings to inform how they promote content.

“There has been a lot of research examining fake news and how it spreads, but this study is among the first to suggest a potential long-term solution, which is cause for measured optimism. If we can decrease the amount of misinformation spreading on social media, we can increase agreement on basic facts across political parties, which will hopefully lead to less political polarization and a greater ability to compromise on how to run the country,” says Rand. “It may also make it harder for individuals to win elections based on false claims.”

He notes that current solutions for fighting misinformation deployed by social media companies haven’t been that effective. For example, partnering with fact-checkers isn’t scalable because they can’t keep up with the rapid creation of false stories. Further, putting warnings on content found to be false can be counterproductive, because it makes misleading stories that didn’t get checked seem more accurate – the “implied truth” effect.

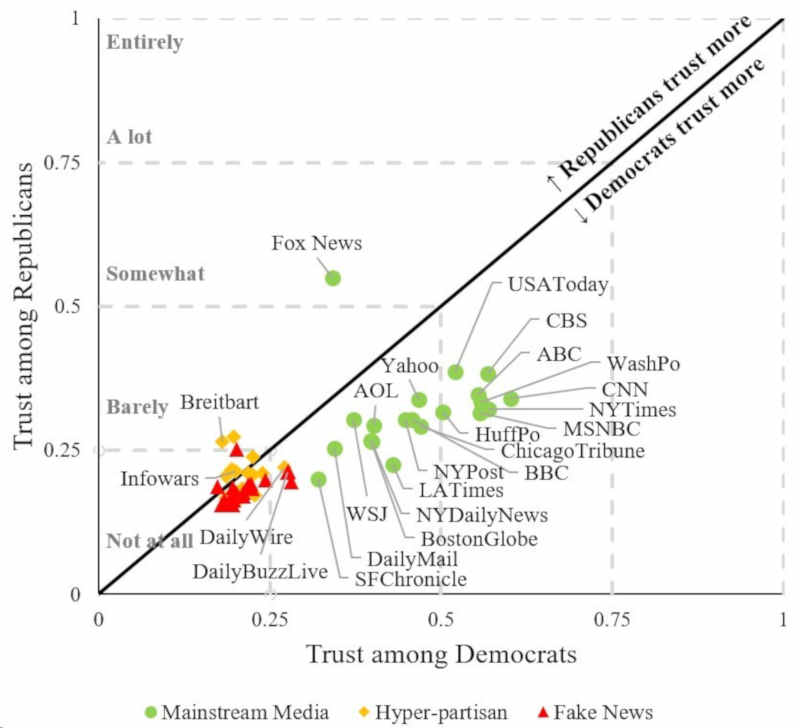

In their study, Rand and Pennycook examined whether crowdsourcing could work as an effective tool in fighting the spread of misinformation. They asked laypeople to rate familiarity with and trust in news sources across three categories: mainstream media outlets, hyper-partisan websites, and websites that produce blatantly false content (“fake news”).

The pool of people surveyed was nationally representative across age, gender, ethnicity, and political affiliations. They also asked professional fact-checkers the same questions to compare responses.

They found that laypeople trust reputable news outlets more than those that create misinformation and that the trust ratings of the laypeople surveyed closely matched the trust ratings of professional fact-checkers.

“Our results show that laypeople are much better than many would have expected at knowing which outlets to trust,” says Rand. “Although there were clear partisan differences, with Republicans distrusting all mainstream outlets (except for Fox News) relative to Democrats, there was a remarkable consensus regarding non-mainstream outlets being untrustworthy.”

For example, the average Republican participant trusted mainstream outlets that are seen as left-leaning, such as CNN or MSNBC, more than right-leaning hyper-partisan sites such as Breitbart, he says. “Findings like these reveal that attitudes towards media sources are not as dominated by partisanship as one might have thought.”

These results suggest that a scalable approach to fighting misinformation is for social media platforms to survey their users about how much they trust various outlets, and then promote content from sites with high trust ratings.

An important caveat is that familiarity heavily impacts trust rankings. Rand explains, “If people are not familiar with an outlet, they overwhelmingly distrust it. If they are familiar with it, then their trust depends on what content the outlet produces. This will pose a problem for relatively new but high-quality sources, so social media platforms may need to provide samples of recent articles before asking if the outlet is trustworthy.” Furthermore, it is also not clear how the study’s results would generalize internationally beyond the U.S.

“Crowdsourcing, if implemented correctly, is a promising approach to fighting the spread of misinformation and false news,” concludes Rand.

💛 Support Independent Journalism

If you find RMN News useful, please consider supporting us.